The OPEC/non-OPEC ministers’ decision last week to increase the September production target by a symbolic 100,000 b/d was a curious one and came in for considerable political post-mortem, though the news cycle quickly moved on.

If it was meant as a gesture to the US in response to President Joe Biden’s latest entreaties to the Gulf producers during his trip to Saudi Arabia last month, it didn’t work. In fact, it was deemed an insult to Biden.

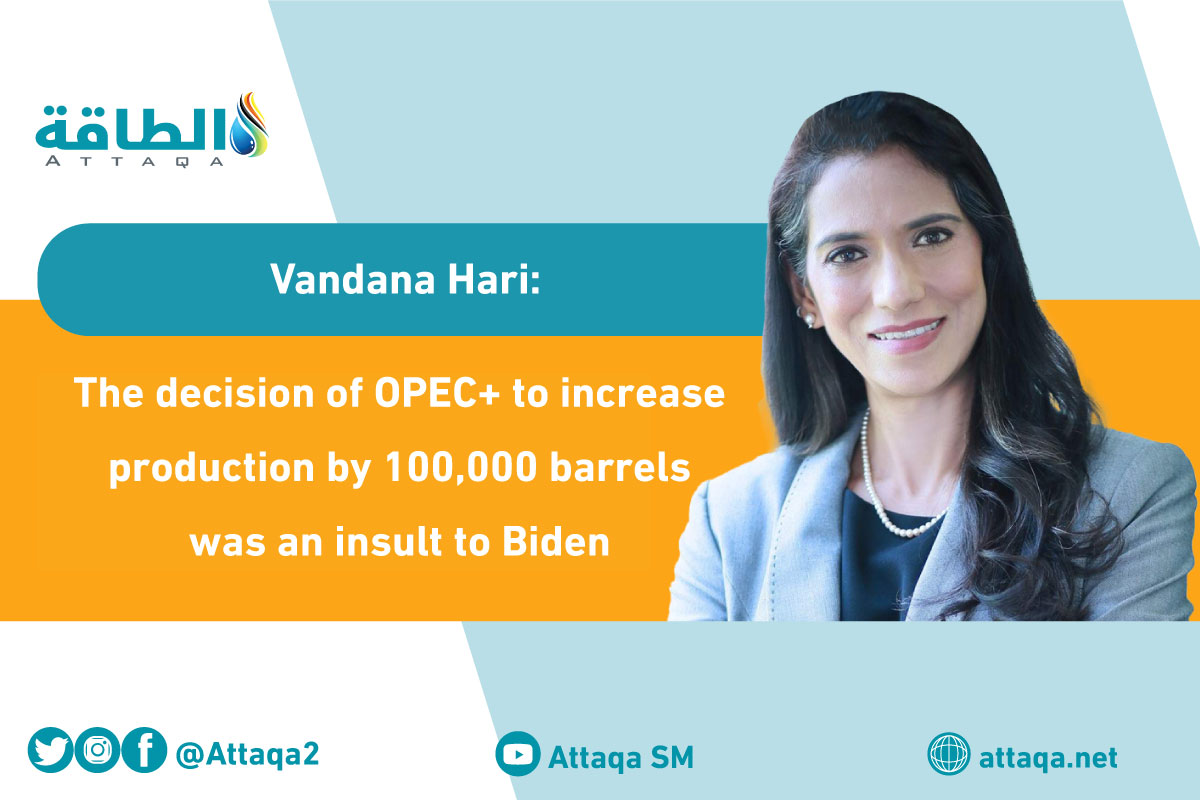

The target hike is even more insignificant than the headline number because even in the best-case scenario, we estimate only about 40% of it would materialise as actual incremental supply, given that the vast majority of OPEC+ members are struggling to meet even their current quotas.

The estimated 40,000 b/d output hike corresponds to the cumulative increase in Saudi, Emirati and Kuwaiti quotas for September, the only members that may be able to deliver a boost.

But that won’t move the needle much on reducing the shortfall of 2.7-2.8 million b/d between OPEC+ target and actual production levels in recent months.

The producers’ snub came a day after the US State Department approved the sale of Patriot missiles to Saudi Arabia and anti-ballistic missile defence systems to the UAE worth a combined of $5.3 billion.

Maybe now the US administration will give up trying to influence OPEC+ policy decisions.

What is more critical, however, is whether Washington (and other governments in producer countries) heard and will heed the bigger message OPEC+ delivered last week on how it sees its role and that of the rest of the world in securing future energy needs. Is anyone listening?

The central bank of oil?

Former Saudi Energy Minister Khalid al-Falih called OPEC+ the world’s central bank of oil, and his successor Abdulaziz bin Salman had concurred with that characterisation as recently as 2020.

But the alliance may not want to continue playing that role any more.

“The meeting noted that the severely limited availability of excess capacity necessitates utilising it with great caution in response to severe supply disruptions,” OPEC+ said in a communique after Wednesday’s virtual gathering of its energy ministers.

The statement not only highlights OPEC+’s concern over its diminished spare capacity, but also emphasises that the producers’ group would like to keep it in reserve for (real) emergencies. In other words, OPEC+ may not be inclined to boost output simply to cool down prices if it sees no major supply shortages.

Ahead of the ministerial meeting, the OPEC/non-OPEC Joint Technical Committee estimated an average global oil surplus of 800,000 b/d through 2022, trimmed from the 1 million b/d it had projected before the July policy meeting, but sizeable nonetheless.

A broken pendulum

OPEC+’s power is its flexibility — an ability to rebalance the market after a supply or demand shock by quickly curtailing output with a coordinated and disciplined approach, or boosting it by tapping into the spare production capacity of its members as needed.

Without the power to do the latter, OPEC+ becomes a one-trick pony.

While most effective spare capacity being concentrated in a handful of the Middle Eastern producers was long accepted as par for the course, the sheer number of OPEC+ members now struggling to even recover levels they were comfortably pumping just over two years ago is worrisome.

Mid-sized OPEC producers Nigeria and Angola are a case in point, with the biggest and most stubborn gaps between their targets and production levels in recent months.

Unintended consequences

OPEC+’s inability to get back on the horse with restoring production should be ringing alarm bells around the world. But thanks to increasingly ambitious emission reduction targets across the globe, oil majors and independents hastily retreating from fossil fuel businesses, and oil and gas projects being starved of funding, the problem sits in a collective blind spot.

OPEC+ was lauded for efficiently restoring market balance after Covid’s unprecedented demand and price crash with a historic production cut of 9.6 million b/d agreed in April 2020. It was a bold move, and it worked. Now it is exacting a price no one had anticipated.

Older reservoirs that lost pressure because of too many wells being shut-in for a prolonged period may never regain it, while a general lack of investment by state as well as private players even in things like the routine maintenance of fields and oil infrastructure may natural declines accelerate and breakdowns become more common.

Not one of the OPEC+ producers has made a major new oil discovery that might offset the declines from existing fields. There is some encouragement for a few members now to invest in finding and developing gas fields to supply Europe as it pivots away from Russian exports, but it remains to be seen if the funding and projects will actually materialise. Plus, that is gas, not oil.

Even assuming that Russian oil production is able to return to pre-invasion levels at some point, the rest of OPEC+ faces a potential permanent loss of 1.7 million b/d of production capacity because the countries simply lack the financial wherewithal to double down on upstream rehabilitation and revival.

Asymmetrical responsibility

“The meeting highlighted with particular concern,” the OPEC+ communique continued, “that insufficient investment into the upstream sector will impact the availability of adequate supply in a timely manner to meet growing demand beyond 2023…”

The inadequate investment spans some OPEC members, non-OPEC, as well as producers outside the OPEC+ coalition, it said.

The message is clear: The few OPEC+ members that have continued to invest in sustaining and raising production capacity should not be expected to bear the brunt of opening the spigots to drive down prices into the future.

It may also explain Saudi Arabia’s conspicuous silence around the recent burst of speculation around its 12 million b/d officially proclaimed production capacity versus what it can actually reach and more importantly, sustain for a length of time. The analyst comments and debates had cropped up just ahead of Biden’s trip to the Kingdom.

It also puts into context Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s statement last month that the Kingdom will not increase its production capacity beyond the 13 million b/d level currently planned for 2027. The comment, which took market participants by surprise, was made in a speech to a GCC meeting attended by Biden on July 16.

Other countries need to invest in fossil fuels over the next two decades to meet the world’s growing energy demand, MBS stressed in his speech.

This bone of contention between the Kingdom and producing countries intent on divesting away from fossil fuels could become a source of lasting friction.

Vandana Hari is Founder and CEO of Vanda Insights, which provides macro-analysis of the global oil markets.

READ MORE..

- Deceptive Solutions for Fossil Fuel Dependence Drive Prices Higher (Article)

- Deceptive Solutions for Fossil Fuel Dependence Drive Prices Higher (Article)

- The Biden Administration’s policies have pushed gasoline prices higher (Article)

- (Article) The Top 5 Reasons Behind Fruitless Energy Policies

- The Biden Administration’s policies have pushed gasoline prices higher (Article)